“Sorry, I’m all out of wishes. Please check back later.”

“Okay, I’ll give you what you want. Just don’t hurt me!”

There is something about red that fascinates like no other colour . Love and passion; anger and triumph; violence, blood and fury—its emotional range is unmatched. No surprises then that red is the preferred colour of so many sports teams and countries. In the Fujian Province of China, where I took this photo in February 2015, the colour red was literally everywhere. Stepping out of a restaurant, I saw this man holding a bunch of red balloons. They were shaped like lambs—a reference to the Year of the Sheep that had only begun a few days earlier. I thought the man’s job lonely; in this small, out-of-the-way town, two hours from the bustle of Xiamen, what hopes had he really of selling them all? It made me wonder about his chances in life; perhaps he was poor and had little education, in which case the balloons may have been his only source of income. But hey, who knows? He may have been well off. All I can do is speculate.

After taking the picture I was reminded of a scene from It in which red balloons feature heavily. The eponymous clown offers children these red balloons, but before they can take one—and of course they don’t want to—the balloons burst, sending blood splattering everywhere. As an eleven year old, I found that movie terrifying. It is no coincidence that today I have no stomach for horror films. The thought of revisiting past demons is too much to bear. After watching It, I’ve never seen red in the same light again. Even something as innocuous as a stop sign has an aura of horror about it, its red face a stern warning to anyone who dares defy its order. It’s almost like it’s the face of It itself, and that It’s saying, ‘If you fail to stop, you’ll be stopped all right’. And then I see the image of smashed windscreens and blood splattering everywhere, and I think, ‘Yep, you’re right, stop sign. I know the risks of not stopping, so I won’t not stop. Just whatever you do, don’t take my blood. I’m a good person, honest.’ And then I turn left, and everything turns out okay in the end, and I was just letting my thoughts get the better of me.

I don’t know why I’m writing any of this; I better stop.

I’ve always been fascinated by Hieronymus Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights (1490-1510). Or at least I have been since 2009, when I discovered it during an Art History class in high school. To my mind, few paintings of any country or era comes close to matching its utter weirdness. At a time when Leonardo da Vinci was dabbling with that most famous of portraits, the one which would secure his immortality, Bosch took a completely left-field turn, creating a fantastical otherworld in which monsters and men seemingly mixed with utter gay abandon.

What makes Earthly Delights so, well, delightful is its seeming inscrutability. Unlike, say, a Raphael, whose paintings are meant to be easy to interpret, Bosch’s triptych looks simply ridiculous. Anyone seeing those frolicking naked humans and strange geometrical shapes could be forgiven for assuming the artist was completely out of his mind; no sane human being could possibly conjure up such bizarre imagery—at least without the use of narcotics.

And yet, according to Laurinda Dixon, author of Bosch, the artist wasn’t a nutcase. If anything, his work was comprehensible to his fellow countrymen, who understood and appreciated the references he made; references which half a millennia has now, regrettably, made obscure. Dixon argues that because we lack the cultural context of 16th century northern Europe, we tend to place our own assumptions upon the work. This is perhaps why the most common interpretation of the triptych is a moral one. It goes like this: the three panels, displayed in chronological order, warn viewers about living a sinful life, which ends inevitably in eternal punishment. Before their transgression and subsequent expulsion from the Garden of Eden, Adam and Eve lived a collective life of bliss, free from the aches and pains that the unleashing of sin would soon bring about. In the aftermath of their fall, the world lost all its innocence: sin became unavoidable; every child became born a sinner, inheriting the curse from their earliest ancestors, as can be seen in the central panel, whose revellers seem to be partaking in a fantastical orgy; but those who partook in sin and subsequently failed to be cleansed of their wrongdoing were condemned to an eternity in hell, where in Bosch’s vision demonic monsters subject sinners to a myriad of horrific tortures.

Although this interpretation makes sense, it still seems somehow lacking. It fails to explain why Bosch included all those strange shapes, or what all the creatures are actually getting up to. Which is where Dixon comes in. She argues that this interpretation is flawed because it views the painting through a post-Victorian, post-Freudian lens. People simply weren’t as prudish back then as they are now, she argues—and not without reason. For example, if we go even further back to Dante, we may note that lust was regarded as the least corrosive sin in the Inferno. When the poet enters the first circle of hell proper, he comes across Francesca and Paolo, an adulterous couple whose flurry of passion outside the confines of holy matrimony condemns them to an eternity of being blown about violently with the wind. And yet their transgression is considered minor because lust, in signifying a lack of self-restraint, makes a relatively minor impact upon society; compared to treachery, which Dante locates in the Devil, which requires the perpetrator to exercise with all their faculties, and whose impact upon society is utterly destructive, lust is simply naive and animalistic. In Dante’s ethical outlook, after all, a sin’s gravity can be weighed by how it upsets society; hence since lust is seen to cause harm mainly to those who partake in it, and to immediate family, it is less serious than, say, Satan’s determination to replace God with himself—a sin for which all hell broke loose.

Anyway, whether Dante’s view was shared by the Catholic Bosch and his contemporaries is moot; but what can be said is that unsanctioned sex was never Bosch’s preoccupation in the first place. In fact, Dixon argues that sex was seen essentially as a holy act that took place not just between human beings, and between animals, but also between chemical elements everywhere. Dixon points out that chemical reactions were regarded as a form of sexual intercourse; chemicals would come together and produce a new, chemical offspring, creating life in much the same way that God originally created everything. And because everything is made up of elements, the people of the time believed that if they combined chemicals in the right way, they might be able to recreate the world as it was before sin had made its entrance. For this reason, alchemy, far from being the discredited pseudoscience it is today, was seriously regarded as a sanctified endeavour. Besides the likes of Newton, who was known to practice the then-regarded science, priests would, during services, perform alchemy in the name of the Lord. Of course, none of their efforts succeeded, for if one of them had, the world would now be as it appears in the left panel: unsullied in every respect.

But that’s not all. For Dixon goes so far as to argue that the central panel only makes sense from this ‘chemical’ perspective. The revellers, far from engaging in wanton sex, are upholding moral standards by propagating the species and bringing more life into the world. This might explain why the people don’t seem to have any lust in their eyes whatever; on the contrary, they seem rather playful and innocent—like sheep in a pasture being tended from afar. Likewise, the people riding horses in a circle symbolise the chemical process, which creates new chemicals and chemical reactions indefinitely. Circles, after all, don’t end, and neither do these reactions. The same can be said of the birds seen flying about in the first panel, who Dixon suspects are flying about in a cycle very much like that of the horse riders.

There are many interesting ideas in Dixon’s book—which makes me annoyed that I can’t remember what she has to say about the geometrical shapes, or how the right panel relates to the other two. But what little I remember of her book I find not just convincing but revelatory. If Bosch was really so transparent to his contemporaries, it goes to show how attitudes and cultures can change so dramatically. It also makes you wonder what people five hundred years from now will make of today’s contemporary art. It’s a pity we cannot find out, but perhaps it’s better that way.

This is a sonnet I wrote in memory of my pet rabbit Tazze (2011-2015). She passed away on Friday 11th September, leaving behind a lifetime of health problems. She was a beautiful little rabbit who warmed the hearts of everyone she came across. I miss her every day, but I’m grateful for every day we could spend together.

Once all this sudden grief has been interred,

And uncompleted regrets put to rest;

Once sobs about her passing cease be heard,

Nor heaviness on our hearts still impressed,

Then we will mark the starry life of one

Who soared in spaces far beyond this air,

Emitting lion roars and epics done,

A rabbit who would every knot make clear.

No wonder then that giants turned intent

To feed her love unfettered, of good will,

For holy eyes alone made one content,

And signalled more than any sum can fill.

Though time may temper this unseemly mood,

Her memory will not ever mine elude.

Whew! It’s been a while since I last wrote my blog. And not without cause: the last few months have been busy, busy, busy. Ironically enough, my blog posts dried up the very moment I began working as a copywriter. Strange though this may sound, given the writing-intensive nature of my job, it does make sense: after spending hours in front of a screen agonising over words, the last thing I want to do when I get home is spend even more time in front of a screen agonising over words. In fact, you could go so far as to say that writing for a living actively discourages writing on the side. I’m sure the same applies to people who work in a fish and chips shop; after inhaling all that unholy oil, fish and chips would be the last dinner idea to cross their mind. As they say, familiarity breeds contempt.

And yet I’m back. And there’s a reason for that. For try as I might to put down my pen and live in mindless bliss, I can’t. To do so is to ask the impossible; my mind won’t permit it. Because however arduous the writing process is, it’s the one thing that keeps me sane. In no other activity do I feel such a sense of relief, as if the weight of my thoughts had been gloriously suspended, for a short while at least. For once recorded, my thoughts have no more need to pester me, for I then know that even if I were to forget them, they would live on right here, on this blog.

Which brings us to this blog post. As a native of New Zealand, a country in the South Pacific, I’ve a natural interest in our flag referendum, which proposes to replace our current flag with a completely new design. As someone with republican sympathies, but who nonetheless acknowledges the stability of our constitutional monarchy—which effectively ensures that no single individual could do a Cromwell and begin enacting draconian laws against the public’s will—I’m excited about the prospect of my country’s taking a leaf from Canada’s book and introducing a completely new emblem. Having taken a history paper on the British Empire while I was at the Sorbonne, I am only too aware of the role grandiose ideas can play in stirring nations, states and tribes into performing the most despicable acts. Hence while I personally love New Zealand’s current flag, it being the only design I’ve ever known, I feel it behooves the government to adopt a design that doesn’t draw so much attention to our colonial history.

Of course, given the way the flag referendum is going, there’s almost no chance of a change of guard. The five alternative designs are so uninspiring that I’d actually prefer to keep the status quo until something better can be mustered. Something with class that speaks to the hearts of all kiwis. Something, in other words, that I myself designed.

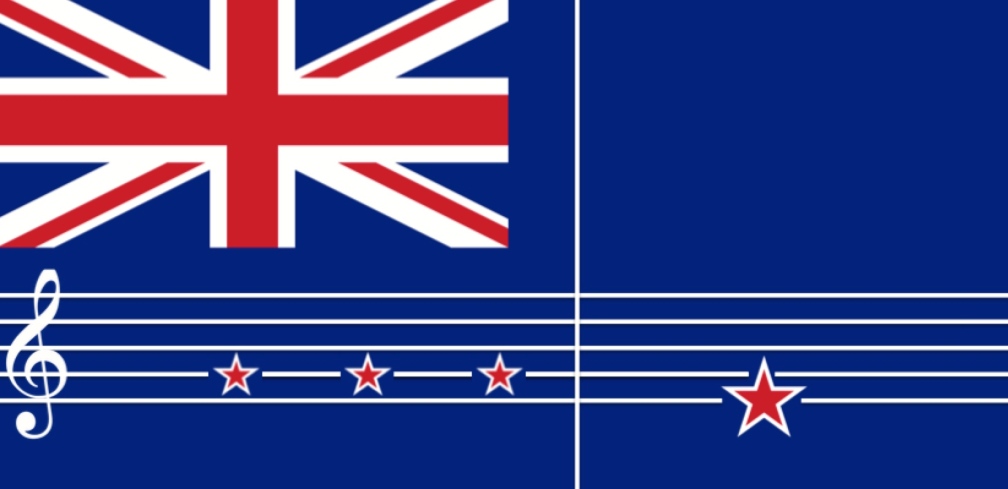

Just kidding of course, but for a while the government did encourage the public to submit flag designs. And because the criteria for entering a design was so low—you were in the clear as long as your design included no words or offensive emblems—I managed to sneak my own creations past the censors. So for my first design, Rule Fritannia, I decided to put colonialism into its historical context. And boy, I think I succeeded:

But it wasn’t all plain sailing from there. My next three designs were rejected, supposedly for breaching design criteria. Somehow, I cannot fathom why this may be so. I mean sure, flags aren’t allowed to include words. But if New Zealand’s flag is constantly mistaken for Australia’s, adding the words ‘Not Australia’ in comic sans may turn out an eminently sensible solution.

The exclusion of the next flag from the referendum was even more baffling. I mean sure, I did simply use a (copyright-free) image from Wikimedia or somewhere like it, but think of it this way: such a flag has incredible educational power. Because it depicts every single country in the world, school teachers the world over could hang it on the wall as a world map, thus ensuring that every child would grow up knowing where New Zealand is (or that it exists).

And ok sure, The Blue Ensign (Dj illuminati remix) may appear unserious on the surface. But hey, we live in a postmodern world, where remix culture is everything!

Alas, my reasons fell on deaf ears. Undeterred, however, I resolved to make my designs subtler—so subtle, in fact, that no hapless government employee would detect the hidden message in my designs. In other words, I had to adopt the mentality of a WWII prisoner scribbling coded messages to compatriots back home. Sure enough, my next flag Victoria survived the unscrupulous scrutiny in one piece. At first glance, it looks like the current flag design, the only difference being the addition of a running track, on which the four stars have been repositioned.

But that’s only because I left out the clef and the bar. Once included, they signal something else entirely—Allegro con brio. If you play the flag on piano, you may recognise the motif because it’s probably the most famous motif in the world. And they appear in Beethoven’s 5th symphony, which is also known as the Victory Symphony. Hence the flag’s name Victoria. What’s even better is that I submitted the design under the name of my rabbit; and because the name of everyone who successfully submits a design is to be engraved on a flag pole in Wellington, her name is sure to echo down the halls of history.

What’s even better is that I submitted the design under the name of my rabbit; and because the name of everyone who successfully submits a design is to be engraved on a flag pole in Wellington, her name is sure to echo down the halls of history.

For my final act, however, I decided to go lo-fi. After seeing the remarkable similarity between the spiral-shaped Koru, which means ‘loop’ in Maori, and the Spiral Hill in Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas, I thought it fitting in my final design to reference the movie.

After all, as everyone knows, a sheep performing yoga in the moonlight atop Spiral Hill in Halloween Town is as kiwi as it gets.

Always dear to me was this lonely hill, / And this hedge, which from me so great a part / Of the farthest horizon excludes the gaze. / But as I sit and watch, I invent in my mind / endless spaces beyond, and superhuman / silences, and profoundest quiet; / wherefore my heart / almost loses itself in fear. And as I hear the wind / rustle through these plants, I compare / that infinite silence to this voice: / and I recall to mind eternity, / And the dead seasons, and the one present / And alive, and the sound of it. So in this / Immensity my thinking drowns: / And to shipwreck is sweet for me in this sea.

For a while now I’ve been wondering why my mind keeps coming back to Giacomo Leopardi’s L’infinito, a nineteenth century Italian poem that I also wrote about last year. It is obviously very meaningful to me, but what is it about its fifteen lines that draw my gaze time and time again?

I believe the reason is that L’infinito conveys a very subtle feeling, one which largely eludes my powers of articulation. It is the feeling of being stuck in a small place and knowing that beyond it lies an as yet unexplored universe. You don’t have to be from a small provincial town to recognise it; anyone who at some point finds their imagination more absorbing than their immediate surroundings can probably relate to it – and that potentially includes the entire human population. Has there ever been a man, woman, or child who has walked upon the earth and thought: “This must be all there is and I, for one, am glad this is so”? No, I sincerely doubt it; for surely, even the most content among us would have once dreamed of seeing more than what they have already seen. To want more is simply to be human.

This feeling is neither good nor bad in itself, but a combination of both. It is good insofar as it points towards new horizons. Had no pioneer ever felt the urge to explore the hitherto unknown, nothing of note would have ever been discovered. But in this strange feeling darkness lurks: if you feel you are not making the most of opportunities while they are yet current, your mind will eventually give way to guilt and anxiety, which as everyone knows are better left unfelt.

It would not surprise me, however, if Leopardi felt these feelings acutely. The poet grew up, after all, in the small provincial town of Recanati and never left the Italian peninsula. Given the extent of his intellectual curiosity and brilliance, his inability to live a life as eventful as Ulysses’ must have proven vexing. To have read extensively on adventures, and yet not to have partaken in any oneself – imagine the hunger! No wonder, then, that Leopardi grew to become disenchanted with life.

The Spirit of Adventure

Now as one who has travelled quite extensively, and with a mere tenth the brain of Leopardi, I couldn’t claim to know the feeling as acutely as he did. In my first two decades, I am fortunate to have already visited around twenty countries, some of which, even, on more than one occasion. What’s more, I’ve even had the experience of spending a day on three separate continents. Let me assure you this: there is nothing quite as baffling as waking up in America, spending the morning in Europe, and going to bed in the Middle East. When you factor in time zones and transit time, the twenty-four hour day ceases to be the certainty we normally take it for.

But in spite of all the travelling I’ve done, I still yearn to travel some more. As much as I love New Zealand, there is no getting around the fact that it is a small country largely cut off from the rest of humanity. Although it is possible to live without ever feeling a tinge of regret for not venturing beyond these shores, once you’ve had a taste for life elsewhere, the thought of staying in one place from the cradle to the grave seems quite frightening. Of course, you could have a diet consisting solely of bread; but once you’ve tasted the finest fruits, the thought of living on bread alone is enough to make you shudder. For this reason it is not the scarcity of opportunities that is the issue, because if you did not have any expectations, you would be quite content with your lot. No, it is having greater expectations that causes the grief, because unless reality lives up to your standards, you’ll go through life dissatisfied, always with the thought that you’re missing out on something.

Going beyond reason

Now I don’t claim to know a great deal about poetry; in fact, you could go so far as to say that I don’t know anything at all. As a humble reader, I simply read whatever novels and poems I think might interest me and then hope for some divine inspiration to announce itself. Rarely does this ever happen; but if the text I’m reading does stick in my mind for longer than it took to read it, I consider the work personally meaningful.

While I don’t know much about Romanticism, I understand that Leopardi belonged to the movement, which was interested in concepts like the Sublime and the awe-inspiring grandiosity of nature. The Romantics were keen on exploring the infinite possibilities of the mind; some went so far as to take mind-altering opiates to enter a kind of mystical experience. While I don’t believe Leopardi was one of these drug-taking poets, he certainly was interested in the mind. Reading L’infinito, I can’t help but think that Leopardi was trying to overcome the physical world’s severe limitations. As the place where he has spent his earthly existence, the ‘ermo colle’ (solitary hill) is dear to him; but at the same time, it is bracketed off by a ‘siepe’ (hedge), limiting his ability to see anything beyond it. This problem is one we are all familiar with. Excepting a small handful of astronauts, we have lived the sum of our lives on the earth, and it is from here that we have formed our understanding of everything. All our thoughts, our emotions and dreams have been formed on terra firma, which naturally limits ours understanding of the universe; indeed, until a few odd decades ago, we had no certainty of what the dark side of moon looked like.

Painfully aware of these limitations, Leopardi recedes into his mind, which is infinitely richer than his view from the hill. Indeed, when we look at the things he contemplates, which include ‘l’orizzonte’ (the horizon), ‘spazi’ (spaces), ‘silenzi’ (silences), ‘quiete’ (quiet), ‘l’eterno’ (the eternal), and ‘il vento’ (the wind), it becomes clear they are all essentially abstract in nature. Lacking in form, these concepts can be understood conceptually but are not easy to make a mental image of, simply because they do not really look like anything.

If you try to picture ‘silenzi’ (silences), what do you see? I personally think of outer space, but this is probably because I associate silence with a dark void where no life can support itself. So in other words, because I don’t have a physical image of silence in my mind, I end up thinking of something that I associate with the concept. The pluralising of the word ‘silenzi’ (silences) is also curious. It is seemingly natural to think of silence as being simply the absence of noise; but the word ‘silences’ implies that there are more than one kind of silence. Perhaps silence can be seen not just as the absence of noise, but rather as the absence of anything. Hence if there is noise in the traditional sense of the word – that is, noise in the outer world being carried along by sound waves – there may also be ‘noise’ in the inner world of the mind. These inner noises may include thoughts, feelings, and ideas – things innate to the human condition, and without which one can barely be considered human. So if these things ever become silent in someone, it means that someone has died.

As far as natural phenomenons go, the wind is extremely abstract: since the wind is invisible, you only ever see it in its action; hence the reason I think of the rustling of leaves when I think of wind. But if you were to take away all the objects upon which the wind blows, would it still be visible? I somehow don’t think so. You need concrete objects in order to see abstract ones. Without the former, the latter are imperceptible.

‘Orizzonte’ (horizon) is another one of those interesting concepts that do not exist outside of the mind. The reason the horizon does not have an existence independent of our sight is because it isn’t a thing in itself so much as what we see when we see the sky touch the earth. Of course, where the earth appears to touch the sky varies depending on where we are at any given time; what may be the horizon for one person, may still be the sky for another. This leads me onto another thought: since there is no line demarcating the earth from the sky, you could say that, inasmuch as our bodies are above the ground, we are always in the sky. Not surprisingly, however, no one cares to think like this. For most people, the sky begins about 100 metres above sea level – anything less and something which is in the sky may be described as being “in the air”, but perhaps never “in the sky”.

As for the expression ‘Le morte stagioni’ (the dead seasons), the reason it is evocative is because it is plural, and not singular. If it were ‘the dead season’, one would probably think of winter, which is an obvious symbol of death, given all the dead-looking trees and hibernating animals. So the fact that Leopardi talks about the dead seasons is all the more striking, for assuming that the poet is indeed referring to the four seasons, one would be forced into associating seasons with death in a way that one might not have thought to do so otherwise. Of course, Leopardi may not be thinking of the four seasons; but even if we think of the dead seasons as being metaphorical, in our minds at least we probably cannot help but ‘see’ images of spring, summer, autumn, and winter, as these are are what come to mind when we hear the word ‘seasons’. But the fact that he then talks about the ‘present and living’ season seems to suggest that this ‘season’ he has in mind is life. Therefore, by the ‘dead seasons’ he may be referring to two periods when one is not alive: the one immediately preceding one’s birth, when one is not yet; and the one immediately following one’s death, when one is no longer. It is only in the brief interlude in between these two infinities that one is alive and able to enjoy the present and living season, but once the interlude is over, one returns to a dead season – this one set to last for the rest of eternity.

Holding Infinity in the palm of your hand

All of these abstract-seeming nouns are interesting because, in their formlessness, they symbolise eternity. If something has a definite form, it means that this thing is confined by its form and is thus finite. The fact that the earth is spherical and has measurable dimensions implies that it is finite and is thus fated to pass away. But silence, on the other hand, does not have measurable dimensions, hence the reason we can imagine it lasting forever. By the same principle, the Bible says that God should never be depicted, perhaps because any depiction would have a silhouette, which would erroneously make someone infinite appear finite.

So by contemplating these formless concepts, Leopardi is trying to imagine eternity beyond the finitude of his lonely hill. Considering that he was an atheist, you could say that despite giving up on God, he still craved for eternity, and sought to find it within his mind. But alas, his attempt is futile: so immense is the concept of eternity that the human mind can only understand it conceptually. Unable to come to terms with eternity, his thoughts drown, leading him to flounder in the sea.

That colossal shipwreck

The word ‘naufragar’ can be translated as either ‘floundering’ or ‘shipwreck’, the latter of which, curiously enough, brings to mind Ulysses’ shipwreck in the twenty-sixth canto of Dante’s Inferno. In this canto, the deceased Ulysses’ tells Dante and Virgil of how he had set out on a final voyage to travel beyond Spain and find the things behind the sun, “where no man dwells”. In fact, Ulysses sails so far westward that he ends up in the Pacific Ocean; and just as he approaches the shores of Purgatory, at the antipodes of Jerusalem, his vessel breaks apart, killing every man on board. That Ulysses almost makes it to the ‘dark mountain’ of Purgatory in the distance is, furthermore, not without significance. It is after all the case that Dante’s intermediate place between heaven and hell exists to prepare Christians for their eventual ascent into heaven by ‘purging’ them of the sins that had still been with them at the time of their deaths. Therefore the fact that a crew of pagans unfamiliar with the Christian gospel almost make it to Purgatory shows both:

1) how ‘virtuous’ human efforts not sanctioned by God can be insofar as the crew managed to reach the other side of the world by their own devices; and yet

2) how ultimately doomed pagan efforts are, for whether one is a brilliant pagan sailor who almost makes it to Purgatory before drowning, or whether one is a hopeless pagan sailor who drowns at the start of the voyage, before any achievements of note can be made, makes no effective difference; for in either case a drowned sailor who had never received God’s grace will end up in hell.

The Ulysses ‘shade’ who makes a cameo in the Inferno never uses the word ‘naufragar’ to describe his shipwreck, but his description of the prow going down until the water has closed over all the crew more than illustrates the point.

Down is the new up

But back to my main argument: in poetry, it seems that the concept of ‘floundering’ in the sea is an apt description of how one struggles – to make peace with the fact that one will one day die. In The Sickness unto Death Soren Kierkegaard describes how man is a synthesis of the infinite and the finite: since we can imagine the possibility of living forever, and have a deep-seated hope that we will do so, the realisation that death is inevitable causes us much distress. This distress he calls ‘despair’, and as far as feelings go, it is one that separates us from animals, who have no concept of living forever, and hence don’t fret about it not coming to pass. Anyway, I found these passages from The Sickness unto Death (trans. Alastair Hannay, Penguin Books, 2008) which I thought may be particularly conducive in our understanding of the poems:

Now if possibility outstrips necessity, the self runs away from itself in possibility so that it has no necessity to return to. This then is possibility’s despair. Here the self becomes an abstract possibility; it exhausts itself floundering about in possibility, yet it never moves from where it is nor gets anywhere, for necessity is just that ‘where’. Becoming oneself is a movement one makes just where one is. Becoming is a movement from some place, but becoming oneself is a movement at that place.

Thus possibility seems greater and greater to the self; more and more becomes possible because nothing becomes actual. In the end it seems as though everything were possible, but that is the very moment that the self is swallowed up in the abyss. Even a small possibility needs some time to become actual. But eventually the time that should be spent on actuality gets shorter and shorter, everything becomes more and more momentary…(p. 39).

….everything is possible in possibility. One can therefore run astray in all possible ways, but essentially in two. The one form is the wishful, the hankering; the other is the melancholic-fantastic (hope in the one case, fear or dread in the other). Fairy-tales and legends often tell of a knight who suddenly catches sight of a rare bird of which he then sets off in pursuit, since in the beginning it seemed quite close, but then it flies off again, until at last night falls. The knight is separated from his companions and lost in the wilderness in which he now finds himself. Similarly with wish’s possibility. Instead of taking possibility back to necessity he runs after possibility – and in the end cannot find the way back to himself. Much the same happens in melancholy but in the opposite direction. The individual pursues with melancholic love one of dread’s possibilities, which in the end takes him away from himself, so he perishes in the dread, or perishes in what it was he was in dread of perishing in. (p. 41).

If these passages reveal anything, it is that Kierkegaard was a firm critic of Romanticism, which he believed encouraged people to run after possibilities at the expense of themselves. It is as if he were comparing the Romantic individual to a drunkard who, in drinking throughout the day, escapes having to confront reality; although the alcohol may create diversions for the drunkard to revel in, it prevents this one from engaging with life enough to do something worthwhile. Perhaps in Kierkegaard’s eyes, Leopardi, by contemplating all these things, is avoiding having to own up to the fact that he will die. But the task he sets himself, which is that of contemplating eternity, is so obviously impossible that, in “floundering about in possibility,” as Kierkegaard puts it, he ends up being “swallowed up in the abyss.”

That sinking feeling

This feeling of sinking is also present in the sonnet When I have Fears that I May Cease to be by John Keats. In this work the poet is fully aware of his mortality and how the passing of time hastens the closing of his life:

I believe this poem shares with Leopardi’s poem a mood of despair, a feeling that in spite of everything, his life will end and he will be left with nothing. The last line reads, “Till Love and Fame to nothingness do sink,” which is similar to Leopardi’s thoughts floundering in the sea in the sense that both describe desirable things being submerged in a liquidy substance that will ultimately be their undoing. When Keats is to die, none of the love and fame he has amassed both in his lifetime and beyond it will be useless to him, because he will not be around to enjoy them. And whilst Leopardi does not speak of love and fame, his thoughts, even if they will be preserved on paper for the benefit of future generations, will not accompany him to his death; for when he dies, he will die alone.

Everybody leaves if they get a chance

Now I believe this feeling of despair is also present in perhaps my favourite song ever, Radiohead’s Weird Fishes/Arpeggi. The presence of so many arpeggios (or ‘arpeggi’ to use the correct Italian plural form) creates a real buoyancy that makes me imagine myself soaring in the skies.

The music sounds really hopeful and promising – until you read the lyrics and realise just how negative they are.

As is always the case with song lyrics, they sound more impressive when sung. If you simply read them out loud, they would not sound particularly impressive; but when sung the way Thom Yorke sings them, they become magical and transport the listener into an enchanted realm where everything becomes possible.

But behind the happy exterior lies a sunken despair that the lyrics are quite not able to conceal. Although being attracted to someone’s eyes may sound like something positive, being turned on to phantoms and falling off the edge of the earth do sound wilfully destructive. Might the ‘weird fishes’ be pangs of despair so great in their intensity that the subject is willing to do anything to escape them? “Hitting the bottom” sounds like floundering in the sea or sinking, if perhaps more forceful in its application than what the aforementioned poets end up doing. When I think about it, Weird Fishes/Arpeggi could easily be the song of Ulysses’ ‘mad flight’ to the island of Purgatory: eager as he is to get away from it all, Ulysses embarks on a final adventure and sails beyond the edge of the then known world, only to capsize and find himself spending an eternity stuck in a small flame in hell.

Just my two cents for the day.

What does your favourite football club say about you? As an Arsenal fan, I’ve always seen my club as the aesthete’s team of choice, what with the stylish play and the London-bred cosmopolitan outlook. By contrast, Chelsea has always struck me as a boorish club supported by boorish people who care more about outward success than decency. To be reductive, Chelsea fans, or at least recent converts of the Blues, are probably part of the same demographic that, if given a chance to attend Hogwarts, would join Slytherin in a heartbeat.

Of course, I’ve not a shred of evidence to suggest that any of this is true, and my prejudice against Chelsea perhaps says more about my envy of their success than anything else. And yet, at the same time, I believe that the type of person who has only recently begun worshipping a club that had achieved very little success prior to 2003, when Roman Ambramovich turned up at Stanford Bridge’s doorstop and started pouring billions of his own rubles into its coffers, simply must be lacking in class. To be frank, no other explanation is possible.

Anyway, I recently came across a website called YouGov Profiles. YouGov is an internet-based market research firm that asks its 200,000 or so members across Britain questions about virtually everything. After stumbling upon the site, I soon realised that its profiles included fans of English Premier League clubs. By typing in the name of a club, I would be presented with a whole collection of data, from where the statistically ‘average’ fan lies on the political spectrum, to what they enjoy doing in their spare time.

To be honest, the data is almost disquietingly specific — who would have known that the typical Arsenal fan’s favourite dish is coq au vin? What’s more, the website is perhaps susceptible to quite a number of inherent biases that render the research rather less than scientific. But just because the ‘facts’ have to be taken cum grano salis, it does not mean we cannot have our fun in the sun.

So to the research:

The horizontal x-axis shows the political leanings of fans of each English Premier League football club. This axis has a maximum of 12 in each direction, with -12 meaning ‘completely left-wing’ and 12 meaning ‘completely right-wing’. By contrast, the vertical y-axis shows the number of fans that each club supposedly has, with a minimum of 0 and a maximum of 4000.

Unsurprisingly, the 5 most popular clubs (in order) are Manchester United, Liverpool, Arsenal, Tottenham Hotspur, and Chelsea. With the exception of Spurs, these also happen to be the most successful clubs in English football that are currently playing in the Premier League. At the same time, the data suggests these clubs have some of the most centrist fans in the competition. This is perhaps due to the fact that their fan bases are larger and more heterogeneous than other clubs. A greater proportion of their fans live outside of the city where the clubs are based, and hence are not as greatly influenced by regional politics. If Manchester is said to be a left-leaning city, the reason this is not reflected in the political preference of Manchester United fans is because most fans do not live in Manchester. Conversely, Manchester City fans are distinctly left-wing, perhaps because City is less popular, and hence has a greater proportion of fans living in its hometown.

However flawed the data may be, I am fairly confident that a truly representative graph would have a similar y-axis to this one. But as for the x-axis, we are entering into unknown territory. Since I’m not from Britain, I have no idea why Sunderland fans are almost Marxists, or why Aston Villa are only slightly to the left of Mussolini. It could be that these clubs have fewer fans on YouGov, thus ensuring that each of their fans’ opinions holds greater relative weight. But according to the data, Sunderland and Aston Villa have respectively 391 and 390 fans — far from being among the least popular clubs. In fact, the least popular club is Burnley with 113 fans, but Burnley fans are no more left-wing than Chelsea fans are right-wing.

The Suit of Clubs

Of course, political preferences are only part of the story. The more interesting bits tell us what the fans are like as people. Are Arsenal fans really that different from Chelsea fans? YouGov thinks yes — but apparently not for the reasons I had thought obvious…

Arsenal

The average Gooner is an 18-24 year old female. She is middle class, works in the sports industry, and has a monthly spare income of £1000. Her favourite dishes are coq au vin, empanadas, and steamed chive dumpling, while her hobbies include writing, chess, and board games. She reads The Guardian and The Economist, and is interested in international news, business & finance, and ‘fashion, design & cosmetics’.

She agrees with the statements ‘I am willing to sacrifice my free time to get ahead in my career’ and ‘I don’t like being told what to do.’

She describes herself as ‘original’, ‘relaxed’, and ‘analytical’. But on occasion she is ‘difficult’, ‘confrontational’, and ‘feckless’.

Manchester United

The average Red Devil is also female, but between the ages 25-39. She is working class, works in advertising, and has a monthly spare income of £125. Her favourite dishes are Shoofly pie, strawberry crumble, and lentil casserole. Her favourite hobby is ‘buying and selling online’, while her interests include ‘people & celebrities’, video games, and football. She reads The Sun and The Daily Mail.

She agrees with the statements ‘I enjoy watching ads with my favourite celebrities’ and ‘I am a telly addict’.

She describes herself as ‘dedicated’, ‘outgoing’, and ‘adaptable’. But on occasion she is ‘fussy’, ‘careful’, and ‘demanding’.

Chelsea

The average Chelsea supporter is an 18-24 year old female. She is working class, works in the sports industry, and has less than £125 of monthly spare income. Her favourite dishes are coleslaw, Ayam Goreng Kunyit, and Tom Yum Seafood Soup. Her favourite hobby is dancing, while her interests include ‘people & celebrities’, ‘beauty & grooming’, and ‘fashion, design & cosmetics’. She reads The Sun and OK! Magazine.

She agrees with the statements ‘I’m usually looking for the lowest prices when I go shopping’ and ‘I use beauty products to make myself look better’.

She describes herself as ‘sensitive’, ‘a great performer’, and ‘outgoing’. But on occasion she is ‘stroppy’, ‘silly’, and ‘miserable’.

Liverpool

The average Kopite is a 25-39 year old female. She is working class, works in the sports industry, and has less than £125 of monthly spare income. Her favourite dishes are Scouse, profiteroles, and bacon sandwiches. Her favourite hobby is playing video games, while her interests include ‘people & celebrities’, parenting, and ‘beauty & grooming’. She reads The Mirror and Look Magazine.

She agrees with the statements ‘I use beauty products to prevent my skin from aging’ and ‘I am a telly addict’.

She describes herself as ‘funny’, ‘sympathetic’, and ‘constructive’. But on occasion she is ‘stubborn’, ‘fussy’, and ‘dependent’.

Manchester City

The average City supporter is a female aged 60+. She is middle class, works in the consumer goods industry, and has £125 to £499 of monthly spare income. Her favourite dishes are Yule Log, Jerk Chicken, and cheese and tomato sandwiches. Her favourite hobby is ‘collecting’, while her interests include ‘beauty & grooming’, ‘fashion, design & cosmetics’, and ‘people & celebrities’. She reads The Mirror and Closer.

She agrees with the statements ‘I find the idea of being in debt stressful’ and ‘I’m usually looking for the lowest prices when I go shopping’.

She describes herself as ‘communicative’, ‘conscientious’, and ‘funny’. But on occasion she is ‘stroppy’, a ‘bad listener’, and ‘careful’.

So — surprise, surprise! — the average fan of each of the Big Five is female. Of course, there have been female football supporters for as long as the game has been played. But for a sport known for its machoistic pretensions, it is perhaps surprising that these clubs are apparently more popular with women than men. As a case in point, the typical fan of the next big club, Spurs, is a male aged 60+, while the average Everton fan is a 25-39 year old male. This may suggest, among other things, that women prefer supporting clubs that actually have a realistic chance of winning titles. But with our limited information, we can only speculate. Who knows? Perhaps many fans simply begin supporting whatever team their parents like, and are stuck with that choice for the rest of their lives, irrespective of how decent their adopted team actually is.

Another thing to note: these fans are incredibly materialistic. Perhaps this shouldn’t come as a surprise, given that developed countries are, by and large, united in their love of the consumer ethos, whereby the unexpended life is not worth living. But the attitudes of these fans do lend credence to the belief that the Kardashianisation of the modern world is in full bloom.

Football Managers

As a bonus, I decided to look up fans of four of the most famous football managers. Say what you will, the managers do appear to embody the very qualities that fans ascribe to themselves, as if to suggest that the latter are made in the likeness of the former:

The average fan of Arsene Wenger is ‘independently minded’, ‘a leader’, and ‘challenging’. But on occasion he is ‘arrogant’, ‘demanding’, and ‘strong willed’.

The average fan of Sir Alex Ferguson is ‘polite’, ‘well-balanced’, and ‘dogmatic’. But on occasion he is ‘grumpy’, ‘abrupt’, and ‘unfunny’.

The average fan of Jose Mourinho is ‘easy to talk to’, ‘relaxed’, and ‘a leader’. But on occasion he is ‘grumpy’, ‘strong-willed’, and ‘demanding’.

The average fan of Josep Guardiola is ‘well-balanced’, ‘sensible’, and ‘polite’. But on occasion he is ‘selfish’, ‘withdrawn’, and ‘nervous’.

Tales of Mere Existence is a cartoon series mostly about life. Made by an American artist called Lev Yilmaz, the Youtube series follows the life of the artist’s alter ego as he goes about living life the best he can. But this cartoon Lev, however, is no one’s idea of a role model; far from living a life of brilliance, this Lev is simply an ordinary guy living an ordinary life, which when compared to casting spells at Hogwarts and catching ‘em all, does look pretty humdrum.

It is the trite side of life that Lev looks at in his 84 or so cartoons, each of which conveys a mix of disenchantment and bafflement. These feelings are evidently well-known to the sensitive young man, whose idealism is in constant conflict with the less than ideal world he finds around him. Indeed, as an outsider who occupies a different wavelength to everyone else, his eye for the mundane in life is unusually sharp. Lev’s withering portrayal of the superficiality of most conversations is chronicled in the video Shut Up, which explores the trouble he has with expressing himself. When talking to people, no matter what Lev says, he cannot, for the life of him, finish a single one of his long-winded sentences, before someone interrupts him. Alas, it seems everyone he knows is piss poor in the listening department. While walking with a friend one day, Lev observes, “You know, I think it’s sort of interesting to think that if a 22-year old John Lennon were to sing Twist and Shout today, he almost certainly would have been eliminated from Britain’s Got Talent.” To which his friend replies, “Yeah, you see that dog over there? It’s a Pekingese.”

Besides his offbeat sense of humour, Tales of Mere Existence is notable for its creator’s unique, low-fi approach to making cartoons, using only paper, pen, and a glass table as tools. Drawing on a piece of paper placed above a transparent table, he captures every pen stroke on the camera placed directly below it. The result is that his characters and objects appear on screen as incomplete silhouettes who are still being brought to life as we look on. Ever so simple, this technique gives the videos a carefree aura that helps make his less-than-flattering thoughts seem that little bit more humourous.

In My Successful Friends, Yilmaz talks about three friends of his who, unlike him, have gone on to lead successful careers. So while the cartoonist faces up to another day of making coffee for his café’s bonkers clientele, his high school buddies are living the American Dream. Not that Lev is jealous or anything. He claims to be proud of these “terrific guys” and hopes that no terrible misfortunes ever befall them, “like coming down with the bubonic plague, or stepping on a landmine, or being attacked by a mountain lion, or driving off a 500 ft cliff into the Pacific Ocean.” Of course, in listing so many highly imaginative and sadistic ways his friends could kick the bucket, Yilmaz suggests he may be a tad more envious of them than he’s willing to let on. Indeed, there are some things money can’t buy; for everything else,there’s schadenfreude.

From the time he tried crossing his legs on the bus while still trying to “sit masculine” so that no one would think he was a girlie man, to the times he tried to be a hipster, to the typical conversation he has with his mother, the sheer variety of stories that inhabit Lev’s inner world is simply staggering. In the age of social media, Tales of Mere Existence is pure entertainment gold, certain to make your life seem that much more spectacular by comparison. Or perhaps not.

What do Jay Z, Osama Bin Laden, and the Queen of England have in common? If your answer is an English football club based in north London that wins trophies almost every (nine years, having not won the Premier League since the 2003-04) season, then congratulations!— you are a true believer. To the uninitiated, Arsenal F.C. is one of the most popular sports teams in the world, with a fan base said to number 100 million.

And of course, when more than one in every 100 people on the earth today is a ‘Gooner’, as the Arsenal fan is called, there are bound to be contradictions aplenty. Where else, but in a football club, could an American rapper, a Saudi terrorist, and a Germanic royal, lay their vast cultural differences aside and congregate in the house of worship that is Emirates Stadium? Before masterminding the downfall of the Wild West, Bin Laden was said to attend Arsenal matches at Highbury, where, presumably, he cheered on The Arsenal (whose founding members worked in a munitions factory that built weapons during the world wars for the British Army, which in 2003 invaded Afghanistan in the hope of bringing him to justice) and compared opposition players to turds.

Although football is not the most popular sport in this country, those lonely souls who follow it know that it is the greatest game in the entire universe. What other sport stirs up such strong sentiments in its spectators? Such was the passion that one Kenyan had for Arsenal that when his team was losing to Manchester United in a Champions League semi-final in 2009, he went home and hanged himself. Of course, while most fans aren’t willing to show that level of dedication to the cause, it remains to be said that outside of religion and nationality, few other communities inspire such undying commitment in its members. I mean, where else— but in pubs and stadiums— do you see full-grown men burst into song (and tears) every week?

Which brings us to Nick Hornby’s Fever Pitch. The autobiographical novel talks about Arsenal from the perspective of the author himself, who seems to regard the club as an intimate lover. After his parents divorced when he was young, he found in Arsenal a community to belong to. From 1968 onwards, he would religiously attend every match at the home ground, sharing in the team’s joys and sorrows as if doing so were his life’s purpose. It is obvious from the first page that Hornby’s fixation is disturbingly unhealthy: as a kid he used to know the names of the wives and girlfriends of the 1971 Double-winning Arsenal team. And on one occasion, while attending a match with his girlfriend, so engrossed was he in the action that when she suddenly fainted, he failed to help her out. Unsurprisingly, the pair broke up not too long afterwards.

If truth be told, the 1992 novel now seems a little dated. In the freewheeling casino that is today’s Premier League, the idea of fans grumbling about players earning a hundred quid a week sounds remarkably quaint. But some things never change; and Hornby’s understanding of the irrational impulses that drives the sports fan (crazy) is stunningly accurate. His offbeat sense of humour and characteristically English self-deprecation also makes this book both the best and the worst book to read on the bus. You don’t have to like football to enjoy this book. In fact, the less you know about Arsenal, the more you’ll laugh.

There is something about death that fascinates the mind to no end. What Hamlet called “the undiscovered country” looms in the background of every living being, promising to strike but never announcing when it will. And while few want to be there when it finally happens, it has to be said that when it comes to remedies for fear, few are as potent as death. Were you to consider the fact that your days are numbered, and that your light will soon be spent, the fears you once had about money and status would quickly melt into air. Put it this way: if you knew you had only a day to live, you probably wouldn’t spend it at the bank.

Accuse me of being morbid, but there’s a time and place for thinking these thoughts. And while that time may not come very often, if you listen to Marissa Nadler’s Songs III: Bird on the Water, you’ll be in the right frame of mind to do so. Every song on the American folk musician’s excellent album is suffused with death, which alongside love is a recurring theme here. But like Sufjan Stevens’ Seven Swans, to which the album bears certain stylistic and thematic resemblances, it is never sad or depressing. If anything, Marissa manages somehow to make songs about death and love eerily uplifting.

The opening song Diamond Heart encapsulates the approach of the entire album, opening with gentle plucking and the soothing singing of an angel whose voice reaches the highest notes with graceful ease. Equally poised are her lyrics, which like those of Leonard Cohen, whose song Famous Blue Raincoat Marissa covers elsewhere on the album, can tell a story with an economy of words. The refrain: “Your father died / A month ago, / And he scattered his ashes / In the snow,” is revealing because it tells the listener that the lover, whom she is addressing, is as dead as his father. Otherwise were the lover still alive, she would have no need to tell him of his father’s passing, as he would have found it out for himself.

The following songs sound just as beautifully haunted, as if Marissa were communicating to friends beyond the grave. Mexican Summer is warm and inviting, but has an aura of nostalgic yearning about it that is reminiscent of Beach House’s Walk in the Park. Another song, Silvia, seems to reference a poem by Italian poet Giacomo Leopardi, but its words leave no doubt as to the character’s fate: “The water is your friend / And down and down and down you go.” In my view, the most exhilarating song is Bird On Your Grave, which begins slowly and wistfully, before rising to the surface with an electric guitar solo similar in tone and eccentricity to the one in Sufjan Stevens’ Sister. It’s a sad fact of life that Marissa Nadler will probably never be as well known as the acts on the Billboard Hot 100, but to anyone who cares deeply about art and beauty, her music will be infinitely more gratifying, and longer-lasting too.